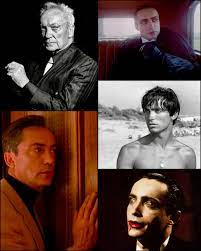

There are actors whose presence simply passes through film history, leaving a faint trail of credits and forgotten roles. And then there are those whose faces, voices, and energies seem burned into cinema’s subconscious, lodged there permanently like dream-images that never quite fade. Udo Kier belonged to this rare second group. He never merely appeared in a film; he haunted it. He electrified it. He queered the air around him. He made even the most ordinary scene feel slightly dangerous, slightly erotic, slightly absurd. Even in a momentary cameo, he could shift the entire gravitational field of a movie.

To write a queer farewell to Udo Kier feels almost redundant. His career was a queer farewell—an ongoing, decades-long love letter to every outsider who ever dared to be strange, beautiful, fearless, or broken in their own way. His very presence on screen insisted on something radical: that queerness is not an afterthought, but a cinematic force.

He was born into chaos, arriving in Cologne at the end of the Second World War, a child of shattered cities and rebuilding nations. That origin story shaped the strange, melancholy electricity that always followed him. Those pale eyes—cool, hypnotic, unreadable—were the kind you might expect on an angel who fell too far, or a tyrant who learned to smile. Kier carried that duality with him his entire life, and it became the essence of his power. He looked like no one else. He moved like no one else. And he acted like the rules simply did not apply to him.

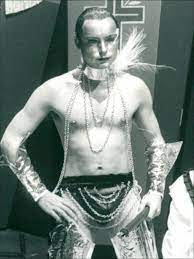

He began his cinematic journey at a time when Europe was finally ready to be strange again. His early work with Andy Warhol’s circle, especially in the decadent grotesqueries of Flesh for Frankenstein and Blood for Dracula, set the tone for what was to come. These movies were queer before queer cinema had a name for itself—sensual, terrifying, humorous, perverse, and utterly without apology. Kier played monsters in ways that invited desire instead of revulsion, pity instead of fear. He embodied queer monstrosity in the oldest, richest mythological sense: the monster who is too beautiful, too wounded, and too dangerous to ignore.

Then came his work with Rainer Werner Fassbinder, which anchored him in the very heart of German queer film history. Fassbinder understood him completely. He knew that Kier could embody the seductive cruelty of power and the aching vulnerability of longing in the same breath. Together they created characters that glimmered with a kind of emotional violence, full of longing, bitterness, and erotic tension. Kier’s face in a Fassbinder film could communicate entire emotional worlds without speaking a word.

And then, just when it seemed he had cemented his identity as a European arthouse apparition, he began drifting into American indie cinema. Directors like Gus Van Sant used him sparingly but with great precision, casting him as the kind of man whose presence changes the air in the room. His appearance in My Own Private Idaho, though brief, became iconic—one of those roles that queer audiences remember not because of screen time, but because Kier made the moment unforgettable. He had a way of elevating even the smallest part into something mythic.

His long friendship with Lars von Trier produced some of the most haunting moments of his career. In Europa, Breaking the Waves, Dancer in the Dark, and Melancholia, he became a ghostly presence, something between an omen and a confession. Kier’s performances in these films were like emotional surgical strikes. He could arrive, deliver twenty seconds of dialogue, and suddenly the entire movie felt charged with unease, sadness, or revelation. He was the kind of actor von Trier could use the way a painter uses the color red—a single gesture that transforms the entire canvas.

As the decades passed, Kier seemed to grow stranger, bolder, funnier, and more willing to leap into risk than ever. His late-career renaissance included the satirical sci-fi absurdity of Iron Sky and the critically acclaimed, deeply unsettling Bacurau, where he delivered one of his greatest performances—ferocious, vulnerable, chilling, and astonishingly human. If anyone ever doubted his depth, Bacurau settled the question permanently. Udo Kier was not a cult actor who occasionally did art films. He was an artist who occasionally wandered into the cult realm whenever it suited him.

People often ask why Udo Kier became such a queer icon, and the answer is simple: he said yes to roles and energies that other actors fled from. He embraced the ambiguous, the erotic, the monstrous, the flamboyant, the decadent, the fragile. He refused to apologize for a beauty that unsettled people. He treated camp as something sacred, something deeply connected to human longing and pain. His queerness was never a gimmick, never a pose—it was the gravitational force of his artistry.

Kier had a way of taking a queer-coded role and imbuing it with dignity and mischief at the same time. He showed queer audiences something precious: that you can be strange and powerful, beautiful and terrifying, campy and profound. He taught us that the world’s edges are where the most interesting lives happen. His performances turned queerness into a cinematic language of power—sometimes dangerous, sometimes tender, always transformative.

Even when he played villains, he made them vulnerable. Even when he played victims, he made them dangerous. He shattered the rigid boundaries of masculinity long before the industry had the vocabulary to describe what he was doing. He embodied the entire queer emotional spectrum—desire, loneliness, rage, humor, tenderness, and that unique, sharp-edged glamour that only queer icons seem to possess.

His death feels like a strange cosmic doorway closing. Kier wasn’t just an actor; he was a mood, a signal, a neon flare sent up from the margins of culture. He was a reminder that cinema needs the outsiders desperately. It needs the ones who bend gender, who flirt with danger, who make beauty frightening, who make monstrosity seductive. It needs people who don’t simply act, but reshape the emotional architecture of the films they inhabit.

We in the queer community feel this loss deeply because Udo Kier represented a kind of artistic freedom that is increasingly rare. He lived as though shame were a myth. He performed as though desire were a kind of spell. His films remain a testament to the idea that queerness is not a footnote to cinema—it is one of its greatest engines.

We will miss him terribly, but the strange, luminous world he helped to build remains. You can still feel him in the shadows of art cinema, in the smirk of every camp villain, in the longing eyes of every queer antihero, in the flicker of every weird, beautiful, unsettling moment on screen. His legacy is permanent. His influence is indelible. And somewhere, in the strange territory between horror and tenderness where he lived so comfortably,

Udo Kier is probably raising an eyebrow at us now—bemused, unbothered, and utterly unforgettable.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.